Links worth investing in: Cash ISAs RIP, small caps, King John and the bureaucratic state, and the next financial crisis (data centres vs student debt)

Weekend reading: I ponder the entangled mess of Cash ISAs, the failing London market and the UK’s dreary, grim reputation

Free for all subscribers today!

Sponsored Content from The Wealth Club: Invest like the super-rich - free guide

It’s been touted as the "best party in town you never get invited to". The rich have been using Private Equity to grow their wealth for years. And overall, Private Equity has outperformed global stock markets over the past 25 years, although that's not a guide to the future. However, until recently it was strictly off-limits to private investors, unless you had tens of millions to spare.

Fortunately, that’s changing - the doors to Private Equity are being pushed open. This free guide from Wealth Club tells you what Private Equity is, how it works, what the risks are… and how you could invest from just £10,000.

Download it here.

Programming note: As we head into the summer, I’ll be taking a few weeks off or switching to weekly notes (through to the end of August). Next week (w/c 14th July) I’m off until Friday but I will be sending out a Links letter as usual at the end of next week. After that I’ll be switching to a weekly note.

The London market, Cash ISAs and the growth trap

I’ve grown increasingly frustrated by the way that in the media and amongst the chattering classes (of which I am a proud member), the issue of Cash ISAs, the growth gap (both for UK PLC and for mid and small sized corporates), the failure of the LSE and Cash ISAs have become entangled into one meta argument.

Put simply, UK PLC faces a problem that requires pulling various levers to fix. Let's set aside the fact that these issues—low productivity growth, an overly cautious investment and savings culture, and funding for growth businesses—are not unique to the UK but are actually quite common across most G7 nations. Our constant comparison to the great US of A makes us feel perpetually inadequate. On top of that, we also compare ourselves to the dynamism of the Great Communist superpower, the PRC : a country with well over a billion hard-working folk that makes us look like a small island principality.

The other thing that annoys me is the quick fix reflex. It goes something like this. The LSE is failing (which it is by the way), so let's dump stamp duty tax on transactions. Or shut Cash ISAs and then herd all the recalcitrant savings cats into investing. Both fixes have their merits, but they won’t address the problems at hand because the big, important issues (low productivity growth) are ‘wicked’, ‘complex’, ‘messy’, and multi-causal. They require a thought-through strategy and compelling presentation to the voting public.

With those beefs out of the way, I’d make some comments on the current debates.

The first is that the Cash ISA is indefensible. There are very few other countries in the G7 that privilege cash savings, except for Canada. Saving is a noble pursuit and I can see why the first iteration of this tax structure, the TESSA, was set up. But savings should be a private matter, with our own incentives and risk budgets. Savings diverted to long-term investment have real macroeconomic value, but that’s not what is happening. TESSAs turned into PEPs and we allowed the language of saving to be confused with investment (taking a risk to fund growth). These tax allowances should only ever have been used to fund investing for growth, not allowing savers to build up a tax free lump sum that in many cases is tens, if not hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Now Cash ISAs are being used to house excess cash which is in many cases declining in real value because of higher than expected inflation (the very definition of long term wealth destruction). We have created a massive savings pipeline to help building societies offer cheaper mortgages. Again, cheap mortgages are a great thing, but they are not the preserve of a simple, easy-to-understand tax regime. And it costs the Treasury real, hard money : the most recent estimate I’ve seen is that the Cash Isa involves approximately £3.8 billion in foregone income, although that estimate was for the 2020-2021 tax year, with current losses to the Exchequer likely to be substantially higher, probably closer to £7 billion. In my humble view, ISA should be about investing, about creating long-term real wealth accumulation, i.e., above-inflation capital growth. Kill the cash ISA completely. Be done with it! Cue a series of angry comments…

What about the idea that only British assets should be in an ISA? This strikes me as a less useful idea. Compelling investors to invest where the government wants them to invest in strikes me as a fundamentally flawed idea and equivalent to all those past schemes where populist governments in Eastern Europe forced local pension fund investors to invest in state pension schemes, often with disastrous results.

There’s a reason why UK equity investments haven’t performed well, and that’s because we – the British economy – haven’t grown fast enough, nor do we have the right mix of businesses to make us attractive to many investors. Fix that problem first, and then the asset allocation from ISAs will follow.

All roads lead back to the growth and productivity challenge, a subject I address regularly in MoneyWeek magazine and in a forthcoming book on the topic. The UK growth challenge won’t be fixed easily because it involves multiple problems, i.e repeat after me, there are no easy fixes. But I would make three observations.

The first is that political and economic stability matters enormously. Virtually every academic analysis I have read suggests that one key component is a stable economic, financial, trading and fiscal framework. Build a consensus among key political players – as the Irish did in the 1980s – stabilise that consensus and then quietly build upon it. It doesn’t appeal to populists who think they have magic solutions and endless levers to pull, but it works. Call it the Swiss way. Patient, evidence-based, consensus-building approaches that promote wealth creation and growth. I won’t dwell on it, but the way we handled Brexit and then Covid hasn’t inspired confidence!

The next observation I would make is that sentiment and narrative matter. Currently, there’s a widespread view amongst many international business and start-up types that the UK is a mess. It's lawless. It's lost its direction. Etc etc. It's wrong, and bone-headed (have these people been to the quiet, crime-free streets of SF recently?), but it's pervasive, especially amongst those who spend far too much time on planes shuttling back and forth between the USA and the UK.

The good news is that symbolic gestures can easily overcome this sentiment-driven narrative. I'm talking here about Big, Popular, Bold moves, which probably don’t make a tremendous amount of difference. So, going against my anti populist leanings, how about a bold move like ‘ zero corporation tax for any scale-up wanting to relocate to the UK for five years’? I’m not convinced it would make a huge difference, and contrary to the howls from the hard left, it would probably not cost very much, but it's worth trying to shift the narrative. Spin the narrative so that sentiment turns positive and smart, globally footloose folk say, “Come to Britain”.

That follows into the third observation: the LSE (the London Stock Exchange, not the august university) is broken. As regular readers will know, I adhere to the view that in equity markets, it's increasingly a liquidity and flow game, with the vast passive wealth accumulation machine constantly spewing out cash to invest in the most liquid markets. And that ain’t the UK. Many small things might make a slight difference, but I’m not convinced any will significantly impact the reality that the USA is a liquidity machine.

But we could carve out our own niche. I’m especially attracted to fund manager Gervais Williams' suggestion that the UK market could become the capital of small-cap listings. Free up the regime for any global business with a market cap of less than $1 billion and allow the world to come here and list, perhaps via a new reboot of the AIM, but with drastically changed rules. Accept that we’ll end up with lots of crap – that’s small-cap investing for you !!

Oh, yes and one last idea. If we do want a lever to pull, then follow up on a suggestion I made in the FT a few months ago. Introduce Business Relief (BR) up to £1 m for pensions, allowing you to stash some of your pension cash away from IHT (remember the rules are changing very soon and your pension will be subject to IHT), but only if it invests in UK private assets (in a tightly defined way to benefit UK productivity growth). In this way, you are not compelling UK investors to invest in something they don’t want to, but incentivising the more risk-friendly to do something for the UK – and avoid IHT.

Factoids

Fiscal drag race: Some tax thresholds have stayed frozen since the 80s, reveals new research from Interactive Investor. The capital gains tax exemption and inheritance tax gifting allowance are currently both at £3,000, the same rate they were in 1981 – 44 years ago. Fiscal drag affects both higher and lower earners, with the personal allowance and higher-rate income tax threshold frozen until 2028. The threshold for the 60% tax trap has been frozen for 15 years – a timeframe that could’ve seen it rise by over £50,000

Future debt crisis – student loans? Apollo’s Tortsen Slok reports that in the US, 45 Million People Have a Student Loan, 24% Are Delinquent. Over here, students don’t default but the government does write off debt. The UK ONS reports that 56% of full-time undergraduate higher education students started in the academic year 2024/25. Only half of undergraduate loan borrowers starting in academic year 2024/25 are expected to repay their loan in full within 31 years.

Source : House of Commons Library Service.

‘Superwood’ factory will press pine into steel-strong panels next month. A startup in Maryland has built a chemical-compression line that turns softwood into bullet-resistant boards that are lighter than titanium, yet stronger than steel, with one-third the embodied carbon of concrete. Backed by US$50 million, including an Energy Department grant, the company is targeting façade and door markets before seeking structural certification. WSJ

The slow-moving pensions crisis. The final report of IFS’ Pensions Review delivers a major stocktake of the UK pension system and finds too many people risk retiring with inadequate incomes, particularly renters, the self-employed, and lower earners. While auto-enrolment has boosted participation, 39% of employees and 63% of the self-employed are still off track.

An Inconvenient Fact: Private Equity Returns & The Billionaire Factory. It’s an old paper now, but it’s still worth reading, Oxford academic Ludovic Phalippou on the PE wealth creation machine (for the founders, not necessarily you and I!).

“Private Equity (PE) funds have returned about the same as public equity indices since at least 2006. Large public pension funds have received a net Multiple of Money (MoM) that sits within a narrow 1.51 to 1.54 range. The big four PE firms have also delivered estimated net MoMs within a narrow 1.54 to 1.67 range. Three large datasets show average net MoMs across all PE funds at 1.55, 1.57 and 1.63. These net MoMs imply an 11% p.a. return, which matches relevant public equity indices; a result confirmed by PME calculations. Yet, the estimated total performance fee (Carry) collected by these PE funds is estimated to be $230 billion, most of which goes to a relatively small number of individuals. If all vintage years are included to 2015, Carry collected is $370 billion, with a performance similar to that of small cap indices, but higher than that of large cap stock indices. The number of PE multibillionaires rose from 3 in 2005 to 22 in 2020.”

Download here

European small caps come back to life. In H1 2025, SmallCap has outperformed in 4 of the last 5 quarters in Continental Europe, according to small cap fund manager Montanaro

Worth listening to : Martin Wolf on the impending US economic fall

I thoroughly recommend listening to the FT’s excellent chief economic commentator, Martin Wolf, in conversation with German-American political scientist Yascha Mounk. It’s free to access HERE. The catalyst for the impending fall is no surprise: the yawning budget deficit. Here’s one key passage:

“….if things continue as they are, the United States is going to have more debt relative to GDP in four or five years than at any point in its history, including after World War II. And it will almost certainly keep going up. This has nothing to do with trade or the supposed wickedness of foreign countries in trade. Because the country is running a huge fiscal deficit, and household and corporate savings are very low, it’s dependent on foreign savings. That means foreigners have to keep buying U.S. debt—a lot of them Europeans, and also the Japanese. And at some point, people are going to say, this is just too risky. Nobody knows when—it could be tomorrow, though much more likely it’s further off.

But once you get to that level of debt—150%, 180% of GDP—and real interest rates rise to 4% or 5%, or even higher, then debt becomes fiscally unmanageable. You get massive inflation. The central bank gets overwhelmed. And here, a crucial factor that could accelerate the crisis is that I think Trump clearly intends to replace Jay Powell with an inflationist central banker. I’m going to assume he’ll tell them to cut rates, just as he’s trying to sell vast quantities of bonds. That could accelerate the crisis significantly, just as, in a very different way, Nixon’s pressure on Arthur Burns in the early 1970s contributed to the great inflation of that decade, along with a few other factors that destabilized the U.S. economy so much.

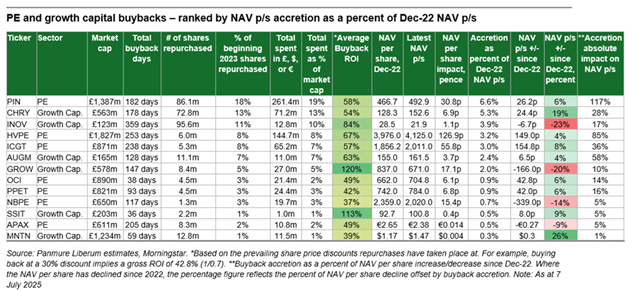

Buybacks have really, really worked for many (though not all) PE and VC listed funds

Panmure Liberum’s fund alternatives analyst Shonil Chande is publishing his latest in-depth note on buybacks later this month, but this week we had a small taster: for listed PE and VC, buybacks seem to work..

“ The ROI maths behind buybacks is more straightforward for capital-growth vehicles. For PE funds, in particular, portfolio returns have been much lower over the past two years. Buybacks are providing a useful NAV growth lever in this tougher cycle. Comparing the most recent NAV per share with figures from the end of 2022, we can see that repurchases have been a core contributor to NAV returns for growth capital and PE funds. This accretion is especially significant for NAV growth-focused vehicles, particularly in a lower return environment for core portfolios. For example, HVPE’s buyback activity has contributed c.126p of NAV per share accretion, accounting for c.85% of its total NAV per share growth since 2022. CHRY and OCI are also worth highlighting. CHRY is just over 70% through its £100m capital return programme, which has added c.7p to NAV and very likely also helped to push up the share price. OCI has been spending a very significant amount on its buyback days, with a strong impact so far.

In some instances, the use of buybacks has been a wasted opportunity, particularly when performance has been ordinary and/or the share price rating is at a discount to peers. One year after seeding its €30m buyback pool, Apax Global Alpha has deployed less than £11m (spending just c.£50k-£60k per day), and the discount to NAV has widened significantly, highlighting that the cautious pace of execution failed to capitalise on earlier opportunities and left the fund more exposed to deteriorating market sentiment. For buybacks or any capital allocation strategy to be effective, conviction and timely execution are essential; otherwise, the impact is weak. A diluted approach to capital allocation, such as underutilising a buyback pool, or spending that is too low a proportion of daily volume/liquidity, has little impact.”

I’d add that there are almost certainly many more buybacks coming in the listed PE and VC sector - watch this space and do some research on Molten Ventures.

The next big financial crisis: data centres

Financial commentator and MIT researcher Paul Kedrosky (who came to me via Noah Smith’s own Substack) highlights what could spark the next great financial crisis: private Credit, AI, and data centres. Everywhere I go, I hear about private credit folks lending money to roll out the next great digital infrastructure boom. Sound familiar to all those other great infrastructure booms, like canals and railways?

“I was struck late this past week by Meta's rumored $29b fundraising for a rapid buildout of more AI data centers. The company is supposedly talking to various private equity firms, looking to structure it as $26 billion in debt, $3 billion in equity…A friend asked me, "Why do that? Don't they have the money?"…[C]ompanies like Meta, which can raise money from banks at low rates any time they want to, increasingly choose ... not to. Instead, they turn to private investment groups—private equity, essentially—who can create custom financing for the project. And for which the company pays a significant premium over investment grade interest rates. How much more? As much as 200-300 basis points, or 2-3%…

So, why would an investment-grade company [like Meta] agree to do that? They do it because the capital needed for these buildouts is so large that doing it with orthodox balance sheet debt, or by issuing sufficient equity, let alone spending your cash, would make a mess of your balance sheet…By structuring it this way, via special purpose vehicles (SPVs) in which they have joint ownership, companies like Meta don't have to show the debt as their debt. It is the debt of those guys over there, that SPV. Not us. Granted, they retain shared control, and they get to use the AI data center, and nothing there happens without their say-so, but still. It's not ours.

This is accounting trickery, of course. It is a transparent attempt to raise large amounts of money without balance sheet damage by putting the debt in a vehicle you indirectly control, but that, for accounting reasons, doesn't have to be disclosed as your debt on your balance sheet…

At the same time, an increasing percentage of private credit providers are funded, in part, by controlling interests in insurance companies, whose capital they use to fund investments. Finding investments that generate higher yields without higher risk—lending at above-market rates to companies like Meta—is exactly what they want to get higher yield while not running afoul of insurance regulators.

And while it all makes perfect sense as financial engineering, this is where the risks start. Why? Because this system creates a powerful incentive loop between structurally overcapitalized insurers, return-hungry private equity firms, and mega-cap companies trying to avoid looking like they're leveraging up. Everyone gets what they want—until something breaks.”

Read more HERE

The making of the English state

Photo Credit: National Trust, Westwood Manor

King John sometimes gets a bad press, but who would have guessed that he’s probably responsible for the founding of the modern bureaucratic state. An extraordinary account here from an LRB article (quoted by Adam Tooze) :

“Across this period (1199-1399) the most remarkable change was in the nature of government. At the beginning of John’s reign, there was little in the way of bureaucracy. There was the king and his household, there were some county officials such as sheriffs and coroners, and there was a small cadre of bureaucrats who ran the three offices of state: the exchequer, the chancery and the curia regis: what we might anachronistically call the fiscal, administrative and legal branches of executive power. But this form of rule was still significantly dependent on the king’s own household, called the chamber, through which his resources as a feudal landlord were funnelled towards government. A straightforward case can be made that John’s personal failings as a ruler, his basic inability to get on with other powerful men, led to some of the political crises he faced. The text of Magna Carta is clear that it represents a settlement to a ‘quarrel’ between the king and his barons. Many other people inserted their grievances into the conversation, however. As well as hallowing the principle that no freeman could be imprisoned except by the lawful judgment of his peers, Magna Carta promised to remove all fish-weirs from the Thames and Medway. In John’s reign, the king, to a large extent, was government: politics could be as simple as trying to get him (or alternatively, one of his powerful enemies) to heed your complaints. By the time Richard II came to the throne in 1377, aged ten, government had developed into an array of institutions whose power extended throughout the realm. The royal courts had become increasingly specialised, with a professional judiciary that staffed two national courts at Westminster as well as maintaining a series of regular peace sessions, criminal courts and civil assizes in each county. Parliament had gone from an ad hoc gathering of major landowners to a regular forum of public debate; it now included a stratum of men drawn from local society, represented in the House of Commons, and it had to be consulted on all major decisions – most critically, on the imposition of new taxes. To publicise and enforce government decisions, the chancery was now at the centre of a huge royal bureaucracy that transmitted proclamations to, and collected information from, every vill in the realm. The office of the exchequer had expanded to take charge of the national revenue; this included the royal chamber itself, which was now forced to account for most of its receipts. Most strikingly, the reach and reliability of the exchequer’s money-raising capacity meant that tax could serve as security for regular advances of credit to the Crown. In 1275, Edward I instituted a new customs duty on every sack of wool leaving the kingdom; it was done at the behest of the Ricciardi of Lucca, who offered a huge loan in exchange for the right to collect this duty for the next two decades. From the 1340s, tax was demanded for the defence of the realm even during years of peace, in order to fund the ‘protection of the coast’ (in fact, it funded aggressive privateering against the French). It became a permanent feature of political life, supporting what the historian Richard Kaeuper has called ‘the war state’. In 1200, the king’s wars were waged by men obliged to fight because they owed fealty to a lord; in 1400, armies were composed of professional soldiers contracted by specialist commanders. They were paid wages raised from a national debt supported by networks of international credit and managed by financiers relying on the collection of regular taxes. By every measure, government had become more complex and diffuse. The king-magnate relationship once central to medieval politics was now one among several of equal importance. The bankers and merchants had to be appeased; so did the squires who staffed the peace commissions in the counties, and the urban elites who governed cities and provided soldiers and ships; so did the village tax collectors, tasked with the unenviable job of getting everyone else to hand over their money.

Source: LRB